Top 6 Issues Patient Safety Leaders Should Focus on in 2021 + Free Tools to Help

The goal of zero harm is achieved by high reliability. Cultivating improved patient safety requires focus on these 6 top issues by health care leaders.

⏰ 14 min read

What are the high-stakes issues patient safety leaders should be focusing on? Where are the biggest risks and the greatest gains with safer care? Patient safety sets a goal of zero harm achieved by high reliability. Cultivating improved patient safety requires a keen focus on cornerstone issues that are initiated by health care leaders. These issues precede and go beyond frontline patient safety events.

A blame-free environment that prioritizes patient safety is the footing needed to empower frontline staff. An organization’s culture will lay the foundation for a successful patient safety program. The culture has to be present first and one that empowers frontline staff to deliver.

According to The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) a Culture of Safety encompasses these key features:

A major change impeding Just Culture is the wide variations in the perception of safety culture within a single organization. A poorly defined safety culture has been linked to increased error rates and diminished reporting. Leaders must be in tune with the concerns frontline as well as determine a staffing level that allows frontline employees to stop and conduct effective “safety huddles” with team members in order to enact change.

Surveys of Patient Safety Culture (SOPS) are useful for measuring organizational conditions that can lead to adverse events and patient harm in healthcare organizations. Safety culture surveys can be used to:

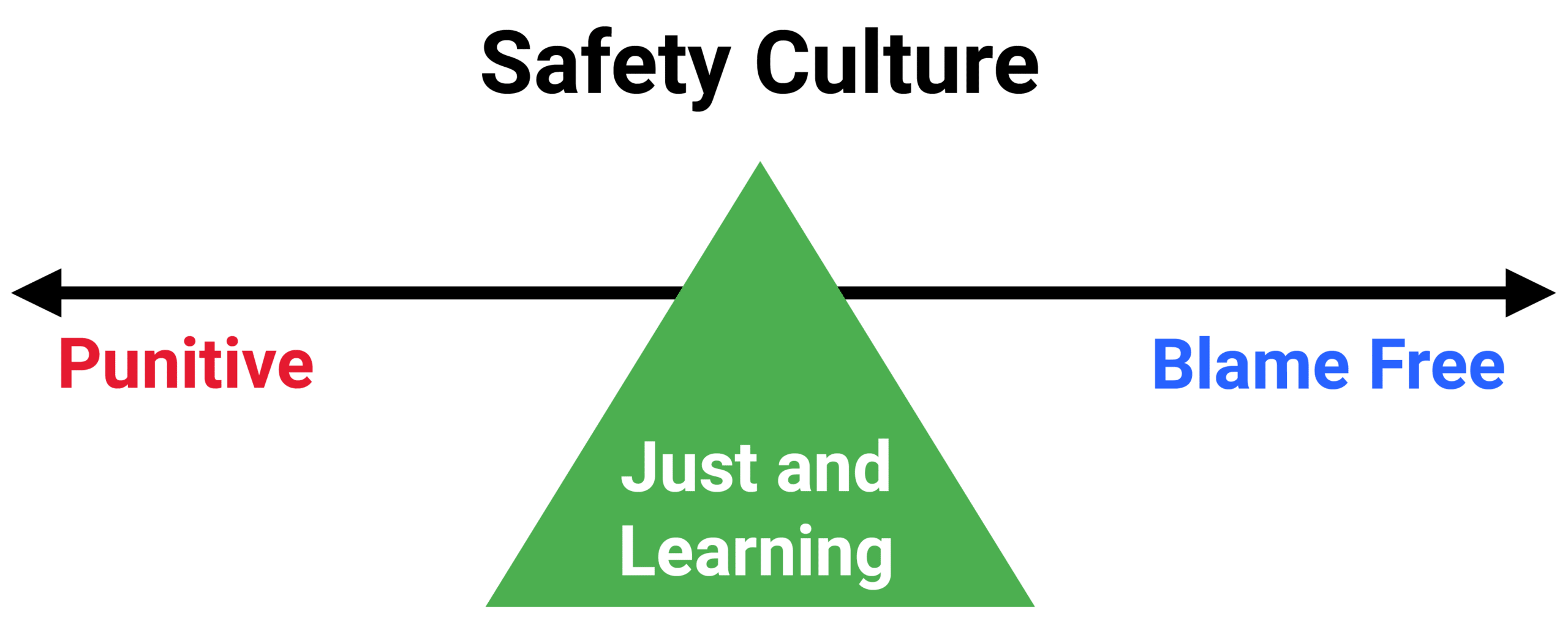

Achieving a Just Culture requires diligent emphasis on quality and safety over blame and fault finding. Safety events should not result in immediate disciplinary action. Instead, it is important to find the root cause and where policy and/or system breakdowns occurred.

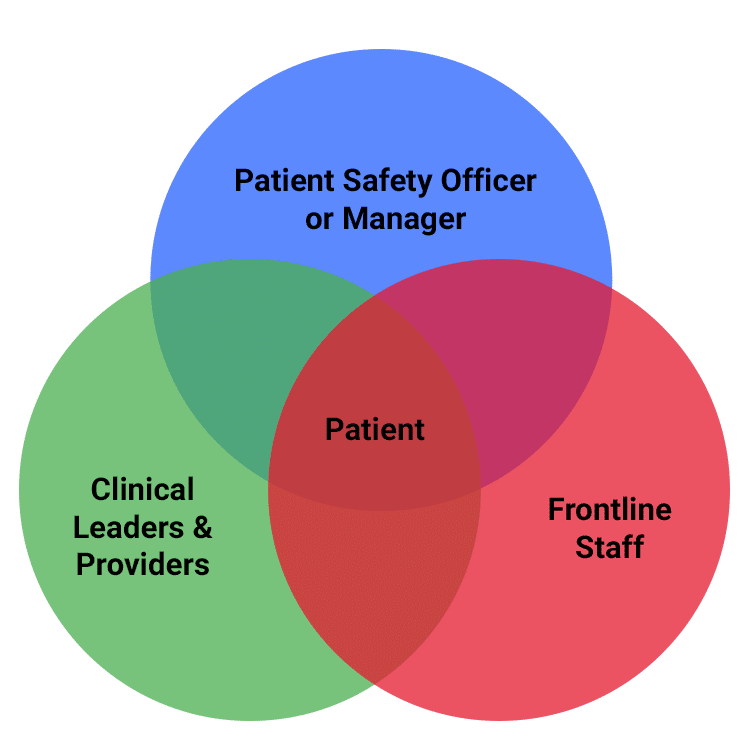

Leaders need boots on the ground to be advocates and resources for patient safety, and this begins with personnel who are in the trenches, handling problems, and overcoming obstacles. Although policy and laws govern patient safety from a centralized system-approach, a better understanding of variation across units within a hospital or across multiple sites within a health system could drive improvements in culture and safety, as well as increase value, coordination, and communication across the continuum of care.

A system’s top-tier management aims to standardize policies across all its patient care areas. While like-facilities may be defining safety the same way (i.e., all have shift huddles, many often use the same products, etc.), variants among sister facilities do exist and some are resulting in better outcomes. Attention to these pockets of excellence is essential in order to shine a light on where best practices exist and why they are so successful. Then, the key is to methodically spread best practices and lessons learned so the improvements can be realized across all relevant areas. For example, Operating Rooms may only be located across the hall but often involve different teams and routines, which can become unintentionally siloed due to the complex, fast-paced nature of the surgical environment. These differences and silos present the opportunity for improved communication and alignment, and when identified as pockets of excellence, can create prime opportunities to share discoveries.

“The fragmentation and variability associated with silo operations is the root cause of inefficiency and the biggest obstacle [to flow],” says Ben Sawyer, Executive Vice President of healthcare performance improvement company Care Logistics. Thinking from leadership to frontline workers should move from individual departments to system-wide. “One of the key mindset changes necessary to break down silos is moving from a focus on immediate needs to a focus on key operational defects,” Sawyer says. One strategy to accomplish this is developing an internal framework that allows providers to address root causes without sacrificing immediate patient needs; in other words, allowing staff the time and space within working hours to brainstorm, collaborate, and possibly pilot system-level improvements. Because complete and competent patient care requires interdependence to be successful, it is imperative that our processes are designed to foster teamwork and communication between all involved stakeholders, from providers to patients.

Patient safety improvement often begins with a retrospective look in order to learn from past experiences, and progresses with targeted interventions that help us do better next time. However, directors of these key departments often omit a crucial step – collaborating with the finance team. Understanding whether an initiative is affordable, or even profitable, is essential to creating a compelling rationale and garnering leadership support. Leaders such as Brent James, former Chief Quality Officer of Intermountain Healthcare and one of the authors of the seminal report from the Institute of Medicine, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Healthcare System, are leading efforts to change the mindset that advocating for better safety tools and more resources or personnel is viewed as a drain on the bottom line.

Prevention using resources to design and implement plans of change can add to the bottom-line and save money. Prevention precludes money loss from lawsuits. And lower risk and less harm help negotiate better insurance rates.

Making the business case to senior leadership for a new initiative, product or service can be difficult. To get started, consider using IHI’s toolkit in conjunction with ADN’s Patient Safety ROI Calculator to prioritize goals and present a solid case for organization investments in patient safety.

PSOs “serve as independent, external experts who can assist providers in analyzing data that a provider voluntarily chooses to report to the PSO.” A strong benefit is PSOs can aggregate data from all of the providers reporting to the PSO. This enables many PSOs to develop the large numbers of patient safety events essential for identifying underlying causes of potentially tragic, adverse events. Working with a federally-designated Patient Safety Organization partner preserves just culture in order to analyze events without fear of legal liability.

Many PSO programs, like American Data Network PSO, integrate adverse event reporting with safety culture assessments and data analysis. The Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005 (Patient Safety Act) and the Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Final Rule (Patient Safety Rule) provide protections that are designed to reduce the increased risk of liability when members voluntarily participate in the collection and analysis of patient safety events. The “uniform Federal protections that apply to a provider’s relationship with a PSO are expected to remove significant barriers that can deter the participation of healthcare providers in patient safety and quality improvement initiatives, such as fear of legal liability or professional sanctions.”

PSOs can answer many critical patient safety questions, such as What factors are contributing to patient safety events or near misses? For which departments or staff should I prioritize improvement? The applications and services a PSO provides can help answer these and many other questions more quickly and efficiently.

Everyone can agree that the first priority following an adverse event is the patient and their family. However, it is imperative not to overlook the involved health care professionals. The Second Victim Syndrome (SVS) is defined as “Health Care Professionals who commit an error and are traumatized by the event, manifesting psychological (shame, guilt, anxiety, grief, and depression), cognitive (compassion dissatisfaction, burnout, secondary traumatic stress), and/or physical reactions that have a personal negative impact.” SVS can affect any provider or discipline in any setting, and it is estimated that nearly half of health care providers experience it at least once in their careers. We’ve recently seen SVS cases related to the COVID pandemic due to a lack of supplies, uncertain care protocols, and overwhelm of systems.

Patient safety leaders need to ensure that the reporting process in place shows concern for staff morale and maintaining Just Culture. Research shows that people responsible for errors feel “called out” even when they are not. Accountability by the organization is important, but individual support is equally vital. Staff need to be encouraged to seek support when an event takes place in order to deal with thoughts of “what will others think about me,” “will I ever be trusted again,” and “have I made the wrong career choice.” These employees mean to do well and are facing complex situations needing validation. Health care systems are creating second victim support programs to help providers cope after adverse events. These programs often involve peer and manager support, as they understand the work and may have gone through similar situations in their careers. Programs are also encouraged to include interventions immediately following the event, as well as on a mid- and long-term basis.

When things go wrong, what is the plan on how to tell patients and families? Adverse events, preventable or otherwise, are a reality of patient care. Disclosure can build patient-physician confidence. Research has shown that disclosure diminishes the risk of a patient pursuing litigation and organization/health care professional ratings tend to be higher because disclosure builds trust. Documentation is important for investigations, which bring about corrective changes.

Disclosure Toolkit and Disclosure Culture Assessment Tool

Created by The Institute for Healthcare Improvement

Many organizations have measured the success of their disclosure programs. The University of Michigan Health System reported a 50% reduction in legal fees. The Illinois Medical Center at Chicago noted an average 50% decrease in legal costs per case. And, one of the oldest programs advocating full disclosure of medical errors is the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Lexington, Kentucky. Once their full disclosure policy had been in place for 10 years, they were able to report that their facility’s median liability payments were one-fifth of the median liability settlements for the private sector.

According to Everett Rogers, a professor who popularized the theory in his book Diffusion of Innovations, “diffusion is the process by which innovations/ideas, knowledge, or processes are communicated among the members of a social system such as a health care organization.” The theory gives an explanation for why some clinical activities are embraced quickly and why others are met with opposition in spite of evidence of showing their benefit. Diffusion can occur spontaneously, simply as a human response. Leaders have the advantage of promoting a culture of adoption. Early adopters embrace and communicate change with their peers. The spread of the new ideas placed into practice (diffusion) can result.

Patient safety leadership focus should be seeking out the biggest risks and the greatest gains in safer care. Focus is sharpened when top safety issues are prioritized. It begins with the culture and looking at every aspect of the organization and using tools to examine the business case for safety efforts. PSO memberships offer protection, additional tools, and answers using your real data. Discovering adverse events and knowing how to care for the patients, families, and affected staff members is key toward moving toward the goal of zero harm.

For more than 25 years, American Data Network (ADN), which is also the parent company to its Patient Safety Organization (ADNPSO), has worked with large data sets from various sources, aggregating and mining data to identify patterns, trends, and priorities within the clinical, financial, quality and patient safety arenas. ADN developed the Quality Assurance Communication (QAC) application, with which hospitals, clinics, rehabs, and other providers record and manage patient safety events. By entering events into ADN’s QAC application and submitting them to ADNPSO, information is federally protected and thereby privileged and confidential. These protections provide a safe harbor to learn from mistakes and improve patient safety.

Resources:

The Ultimate Toolkit for Quality & Patient Safety Professionals Who Wear...

The Ultimate Toolkit for Quality & Patient Safety Professionals Who Wear...